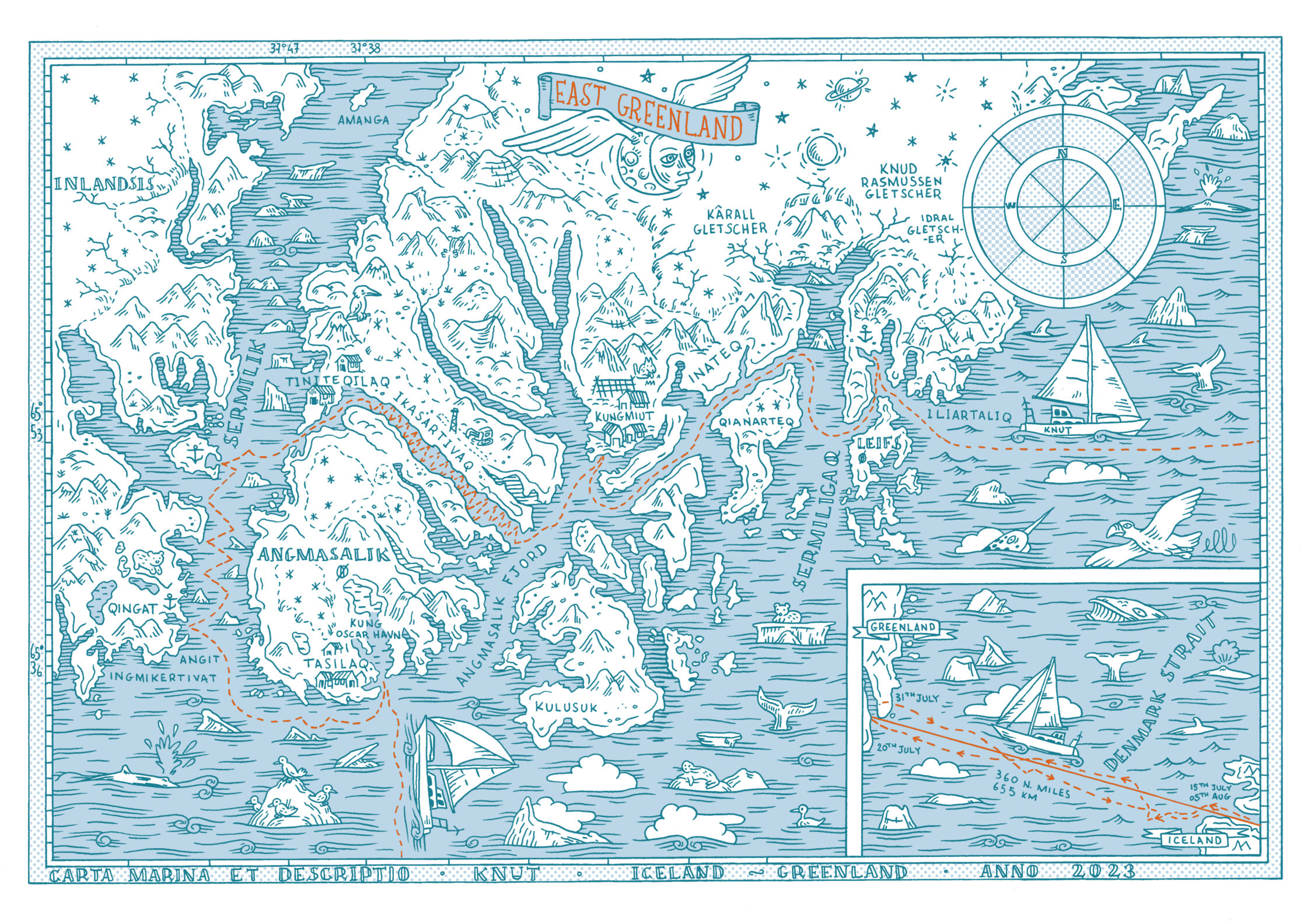

Sailing from Isafjordur to remote east coast of Greenland, July 2023.

A Knut/Marémotrice expedition told by Inaniel.

Remember that even a small block of ice of one cubic meter weighs one ton, it floats really close to the surface, almost invisible. We don’t want to hit that, even at 2 knots, so keep your eyes wide open. Always.

OK…

And when you’re motoring to pass some brash always put the engine on neutral, a small piece of ice could easily break our propeller. »

Ben didn’t tell me a lot more than that before he let me take the helm of the Knut, an Italian sailboat from the 80’s, an offshore race boat made of aluminum that he transformed into a polar exploration boat ten years ago. Low on water, narrow angles, grey with some touch of vivid orange color to be seen from afar, solar panels fixed all around like an old soviet satellite, Knut could come from the movie Mad Max… with an environmentally friendly twist.

We’re in Isafjordur, north-west of Iceland, it’s mid July and we’re getting the boat ready to cross to Greenland. Last time we saw each other it was in 2021 on top of the « Roque de los muchachos », the peak of La Palma island in the Canaries. Ben was moored with his family and Knut on the west side of the island. I was with mine and our sailboat, P’tit Su, in the harbor on the east side. We had decided to meet at the top, him running and me biking my Brompton folding bike. 2700m+ to the top, no shadow on the last two thirds of the road. We were sweaty when we met next to the crazy astronomical observatory. We complained a bit about the heat, had a look at the crazy view, made a joke or two before we went back home, me tense on my folding bike that I had a hard time controlling going downhill, Ben in his agile mountain runner style.

No sun in Iceland though while we’re waiting for the four artists that will join our expedition. The small town is grey, foggy, rainy, and windy. We compulsively look at the weather report and at the ice charts, none of which are good. The ice is still blocking access to most of the Greenlandic east coast and the wind is strong, too strong to go tacking for several days with 4 people who have never sailed before.

That’s what Ben explains to us later while drinking beers in the warmth of the Dokkan – the nicest brewery in town, our repaire here.

The four artists are listening carefully. The full team is Megan Broughton from California, an ice lover, who does etching mostly, Lucie Palombi from Montreal, another etching lady, one of the most scrupulous I’ve met, Claire Frachebourg from Switzerland (though she says that she comes from another planet and that her people will come soon rescue her – which we are all ready to believe after one month by her side) works mostly with sounds and makes music and Christian Bovey, another Swiss, a fascinating illustrator, a good cook and a diphonic singer.

We have never met before and we’re going to spend one month in the small space contained in the 15m of Knut. The expedition is organized by Maremotrice, an association that runs artist residencies and brings skiers and runners to remote polar places, up north where it’s cold and there’s nobody.

On the 15th of July we finally have a good weather window and the ice chart says we may pass. So we go. Humpback whales come to say goodbye jumping around the boat, and we leave the fjord to the open sea. We knew that we would hit the end of the low pressure system we had been avoiding but we had no choice, we needed to have at least one day of wind in order to move before to got glued in the calm weather. It’s a good start, there’s waves, wind, we’re closehauled, Knut speed sometimes goes to 11 knots and during the first 24 hours we don’t see a lot of people on the deck. In fact, in these conditions the best spot is to be laid down in your bunk, waiting for the seasickness to pass. And as it pass, calm weather falls on us. By waiting out the light wind, it was a risk we would experience no wind at all. And that’s what happens. In this case, most other sailboats do what we call «diesel sailing». We don’t.

First, we don’t have a diesel engine and our electric engine doesn’t allow us to motor for miles plus, Ben always says «A boat has sail, it’s made for sailing». Which tells you a lot about Ben. So we sail. For five days. When conditions are good, this crossing takes 2 days. We fight for every breath of air, trying to make the spinnaker fly in the lightest air possible, moving the boat at two knots, sometimes one, sometimes less.

«As long as we’re not going backward we go on» becomes our motto.

On the third day of the crossing, we see our first iceberg. It’s a beautiful small white and blue island covered with petrels. But more than its colors, it’s the sound that it makes that impresses me the most.

The iceberg breathes in the slow motion of the swell. Inhale, exhale.

Like the breathing of a whale but with something more crystalline in it, says Megan. Claire already has her headphones on, microphones in her hand and stuck out over the waves yelling a brief “Silence deux minutes!”

In the summer, when there’s no wind, there’s fog. And we’re in it. And now that we have seen our first iceberg, we have to be extra careful. We snap on «Ice watch» mode. We’re now two people on watch at the same time, one sailor and one artist, one of them outside in the cold to have a good view of what’s going on, the other one in the doghouse ready to take the helm to avoid whatever could be on our course. Being on watch is funny… if you have a strong sense of humor. It mostly consists of staring into a milky void, night and day, until your eyes burn looking for a potential floating white island that could be here. And, when I say night, we have to be agreed, there’s no night! During summertime at these latitudes, the sun never really sets. In this fog, in this constant light, the concept of time disappears.

The rule is «Sleep while you can, eat when you can».

The rest of the time, stare at the void until you hallucinate, until you see ghosts coming out of the fog, sometimes those ghosts are icebergs bigger than a two story house right here at the bow, and you have to jump on «Hector» our autopilot to avoid the crash. Some other times ghosts are icebergs that you hear breathing and thundering when they capsize.

When we don’t hear the ice, we smell it. At sea, far from the shore, smells are getting stronger. I had already noticed on other sails that after a long crossing we often smell the shore before we see it. I remember vividly in 2020 sailing on P’tit Su, during our approach to Madeira after 4 days at sea the smell of the desert, of the hot sand.

But ice smells like rust, like wet iron, an old freezer, a powerful smell, not really pleasant, that reminds us that, even when we don’t see them, ghosts are here looking at us pass by. “It’s like sneaking into sleeping giants bedroom” says Megan. I don’t know what kind of giants they have over there in California but I have to admit that somehow it makes sense.

Nevertheless, this calm weather lets the artist live a quiet life. Knut is a floating library, the shell in the galley is covered with books. Quickly, first as a joke, we formed the Arctic Book Club. We read and debate about literature. Ben gives us advice on his favorite books, we drink tea and coffee while eating chocolate and cakes, lying on the sharkpatterned cushions in the warm air of the boat. After three hours of ice watch outside, working on the sail, winching, tacking in the cold and the fog, getting into this English tea room where four artists exchange their views on Baricco, Marquez, or the last book they read was something a bit unexpected.

There’s not a lot of wind but we maneuver and steer a lot. On the 20th of July I write in my notebook that I haven’t slept more than 8 hours during the last two days, but we’re getting close. After 5 days and a big detour to go around a thick belt of ice, Greenland appears magically from the fog as huge brown and dark green mountains. We had to use the engine to cross the ice pack, and so our first concern is to charge our batteries.

We head to Tasiilaq which is the biggest small town on the East coast with a bit more than 2000 inhabitants. We pass in front of the dump that goes down to the sea, we turn left to a small harbor and dock along a huge pier. Above our heads, a docker drives a huge Caterpillar crazily, moving containers from one side of the quay to the other in a cloud of smelly exhaust fumes.

The town of Tasiilaq is made of wooden prefab houses in vivid yellow, blue, and red, built on the gentle slopes of two rocky hills between which a small river flows. In front of the houses there are fish dryers, whale bones, and most of the time a lot of things that could be useful someday, like an old skidoo, a broken outboard engine or pieces of a washing machine. Sometimes the remains of a dead seal and some rifles are there on the small wooden terrace near the front door.

I go by the small supermarket that sells avocados, oranges, fishing gear, engine gear, ammunition, guns, and lollipops and climb toward the red and white church. A bit further on my right side is the cemetery where each grave is marked with a white cross – all the same – and nicely adorned with colorful plastic flowers. On my left side is the synthetic football field where two teams are playing. Most of the spectators watch the game from their pick-up trucks, where it’s warm and away from the mosquitoes. Mosquitoes! It will take us some time to get used to them, coming like a cloud, attacking every single piece of skin they can find. Football is a big deal around here and the game is being followed really seriously. Spectators honk and yell at each goal and nice action. A bit further out of town a space is dedicated to the sled dogs. Chained in a field, they’re waiting for the winter to be useful at something. Sometimes, in some villages, they put the dogs on small islands where their owners go by boat to feed them with raw meat. Those dogs are impressive, closer to the wolf than to the dachshund. Like the wolves, they don’t bark but howl. And the howling of one pack answers the howling of another pack echoed by the mountain in an impressive concerto.

A small path starts near the cemetery, and according to Ben it’s the only one on the east coast where we don’t need to be worried about polar bears attacking and where we can walk freely, without a rifle over the shoulder. Unfortunately, at the entrance of the path, a sign indicates that a polar bear has been seen two days ago and that «bear protection (= a gun)» was mandatory. We’ll go all together later, walking in a single file behind Ben and his gun. Even with the gun, we cannot go further than 5 meters from each other during the walk.

When the batteries are fully loaded, the crew cleans (showers consist of two boiling pots of hot water that we spill as we can on our naked body outside, one to get wet, the other to rinse ourselves. Later on in the trip, we will improve this technique by jumping straight in the cold sea.

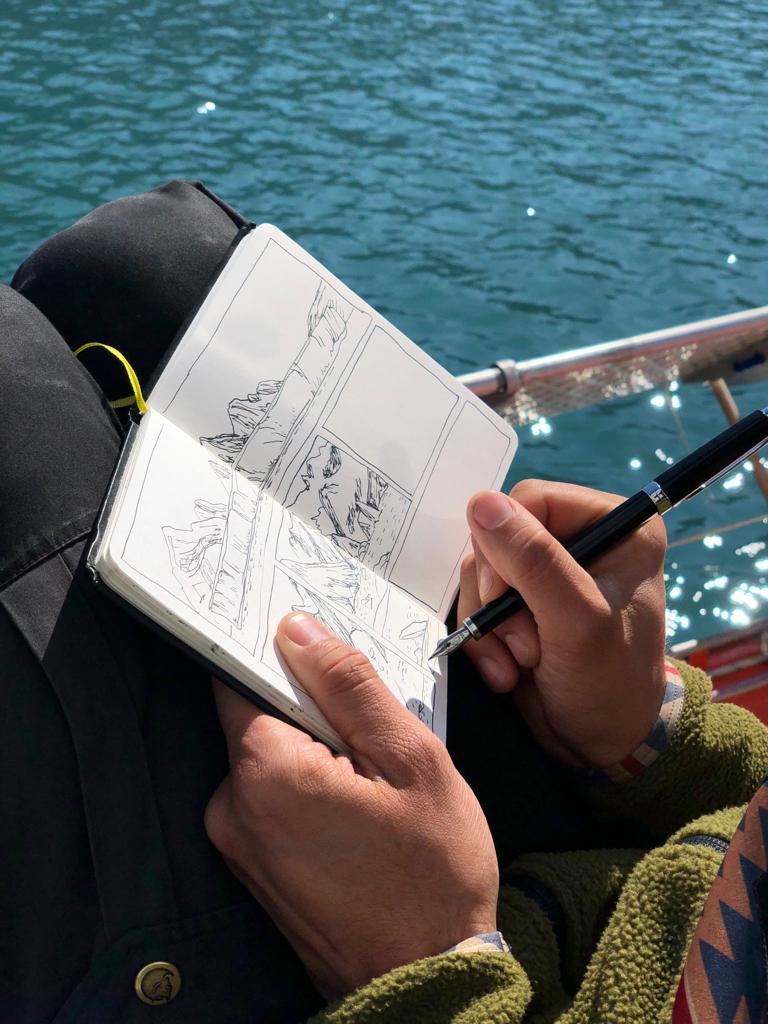

At work. Photo Megan Broughton.

We leave for our first anchorage in Sermilik fjord. Still fog and no wind. The shots of seal hunters and the noise of their outboards rhythm the day between whale breaths and iceberg thunders. Greenlandic people are hunters, apart from some berries and some roots, nothing grows around here.

When they’re back at their village, the seals will be gutted on the beach, the innards will be thrown to the puppies playing next to a whale skull. Bones everywhere, along the bays and along the paths.

Back into the fog then. And for more fun, our GPS tracker isn’t tracking us really well on the map. It indicates that we are currently sailing on one of the mountain peaks at 800m of altitude. We will use our eyes to navigate then, and the map with the few indications that are still useful.

That’s how we make it to our anchorage but we need 3 maybe 4 more hours circling around that bay to find a good spot to put the anchor, with good depth and away from the drifting ice. When the anchor is finally set, we enter the boat where the smell of good food floats in the air, the table is set but the whole crew is sleeping in the galley. It’s 2 AM. “Hey, we are lucky it isn’t windy outside or we would still be out there!” says Ben. Another day, around Petersen Fjord, we have to put the dinghy in the water to check the depth manually to see if Knut and its 3m draft can enter the anchorage. And another time, around Ikateq, it turns out that the anchorage marked on the map is not an anchorage after all and we sail 5 more hours to the next one.

When the boat is anchored and the crew has rested, we go onshore and choose a small peak to summit. From the shore, the three Swiss discuss the way they want to make it to the top and we climb, making our own path, in the dust of the Swiss. The mountain looks like the Alps above 3000m. The vegetation is rare, flowers are nice but so tiny, the moss is thick and spongy, lichens, snowfields here and there, loose scree that is hard to pass over, beautiful drawings of veins in the rocks, crystal pure lakes and waterfalls.

Talking about waterfalls. My poor skull still remembers the day when we decided to shower under Kangertivartikajik waterfall.

Crazy cold water, straight from the glacier hitting our heads, making us groggy, delirious and happy. From the summit, we look down at Knut, resting on the turquoise water, we draw and take some pictures before going back down. Back to the boat. Back home. Where we’ll light a wood fire in the small stove, bake bread, and some will read, some will paint or carve linoleum in a studious silence.

Two days at anchor, one day of sailing, two days in a small village here is more or less our routine. We don’t see a lot of people, but we see a lot of icebergs which we get close to, too close, we go around them to study every angle of them.

We’re always too close to an iceberg if it decides to capsize but Claire wants to record the sound of one without any extraneous noises (“extraneous” being “the rest of us on the boat who never stop talking.”). So one day Ben drops her off in a drysuit on a small one that looks as stable as it can be. The recording of the breathing that she captures is crazy.

Most of the time the weather is OK, the sun rays make it through the fog and we can even have enough wind to sail. But on the 28th of July between Tiniteqilâq and Kungmit, we tack 41 times in 10 hours, in order to get out of the narrow fjord called Ikâsartivaq.

We couldn’t motor that day because our batteries were very low. In Kungmit we dock alongside a barge full of wooden pallets. We have to climb this unstable pile of wood and rusty nails to reach the quay where we find what could be a plug, but we don’t have the right adapter. Exhausted, and past midnight, we make one instead, with Ben barfing nervously and wondering if our DIY plug will explode and whether it will set the whole town on fire first or the Knut.

DIY. When you sail, you spend more time fixing stuff than adjusting sails and really sailing. It’s the routine.

There’s always something to fix. I will spend one afternoon in one of the storage compartments at the back of the boat, upside down, butt and legs under the rain, head really close to an aluminum rail that needed to be cut in order to avoid condensation from leaking inside Lucie’s bunk. Another time, we made two wind vanes to replace the ones that didn’t survive last winter storms. At anchor, I climb the 18m mast of Knut to fix the one we just built from a carbon arrow we found on the beach. From up there, I see some whales breathing behind the small island that protects us from the fjord where, pushed by the current, icebergs are slowly passing by, like white cars on a highway during a traffic jam. They’ll go all along the east coast of Greenland. The biggest won’t have time to melt before they’ll get stuck in the pack ice in late September.

On the first of August, we leave. A little hastily, which people are sad about. A high pressure system that has been on our radar for some days seems to take shape bringing… no wind. Again. Trained to maneuver, we start a gigantic slalom with the spinnaker unfurled, going between the bergs at 9 knots. It’s fast and we often check with each other and with Ben to confirm that maybe – one more time – we’re at the limit of what is reasonable.

But we keep speeding east through the ice as Megan barfs her fucking brains out. The vibrations of the hull and the sound of the water along the hull are exhilarating, in particular in mine and Ben’s cabin at the bow of the boat. I’m on a break, half asleep when the sound of ice rubbing the hull harder than usual makes me jump out of bed. I rush outside, worried, to check what we just hit. «Just some Brash» says Ben, smiling at my face.

Behind him, thick fog is already hiding the shore like thick curtains we closed on our way out.

Greenland has disappeared.

Words by Inaniel

Marémotrice: maremotrice.ch

Claire Frachebourg: clairefrachebourg.ch

Megan Broughton: meganbroughton.com

Lucie Palombi: ateliercirculaire.org/project/lucie-palombi/

Christian Bovey: christianbovey.ch

Inaniel: inaniel.com